We give our lives meaning and weight by the stories we remember. This has become more difficult with scattered families and friends, and with the blizzard of media that is available every waking second. It has become hard to hear ourselves think and to remember that we have stories to tell that make up the fabric of our lives.

One of the few places of respite is hiking, where the mind is able to focus outward instead of re-exploring the details of frustrating work lives and relationships and politics. Even better is to spend time living in a fire lookout, where the focus is on looking at the vast panorama visible from a peak. Working as a professional lookout is a scarce job these days, but there are opportunities to visit lookouts. There are lookouts that people can rent just to enjoy the sensations of observation and isolation. There are also lookouts where people can volunteer to spend days looking for smokes and greeting hikers. Either opportunity gives people time to experience the solitude and wonder of being in a place apart.

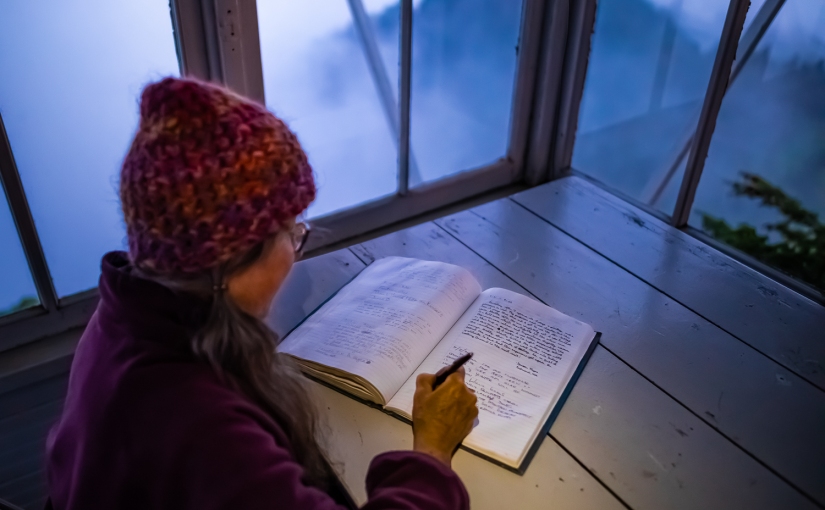

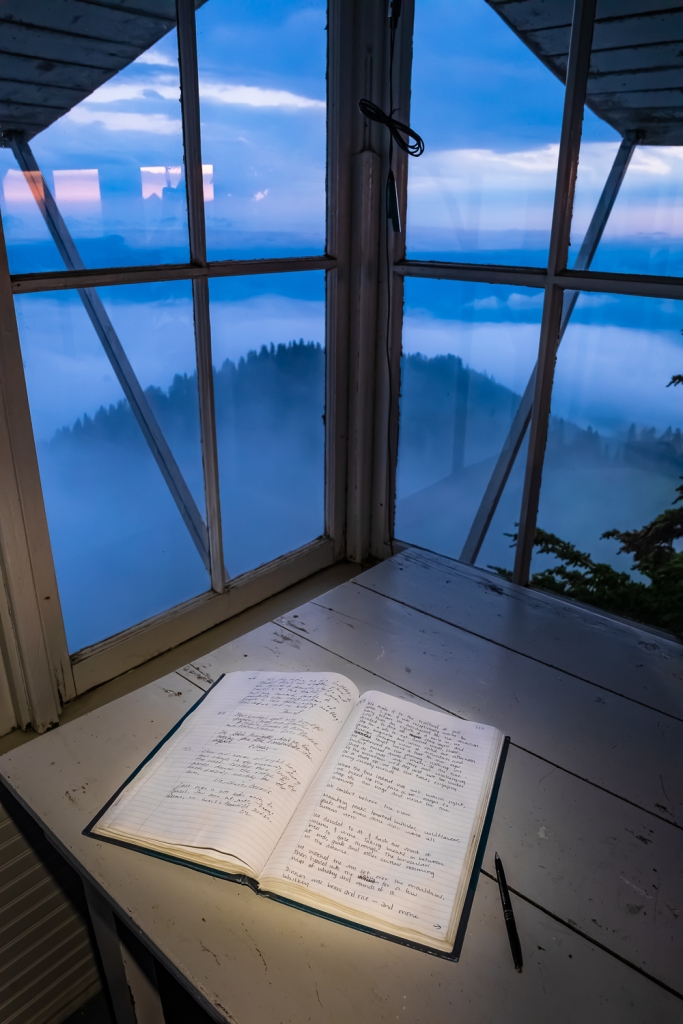

When we rented the Evergreen Mountain Lookout in August of 2022, we experienced the quiet and intimate setting we so desired. Life was simple there for two nights, with watching the stars and clouds, and waking up to the lookout hidden deep within fog. It was wondrous.

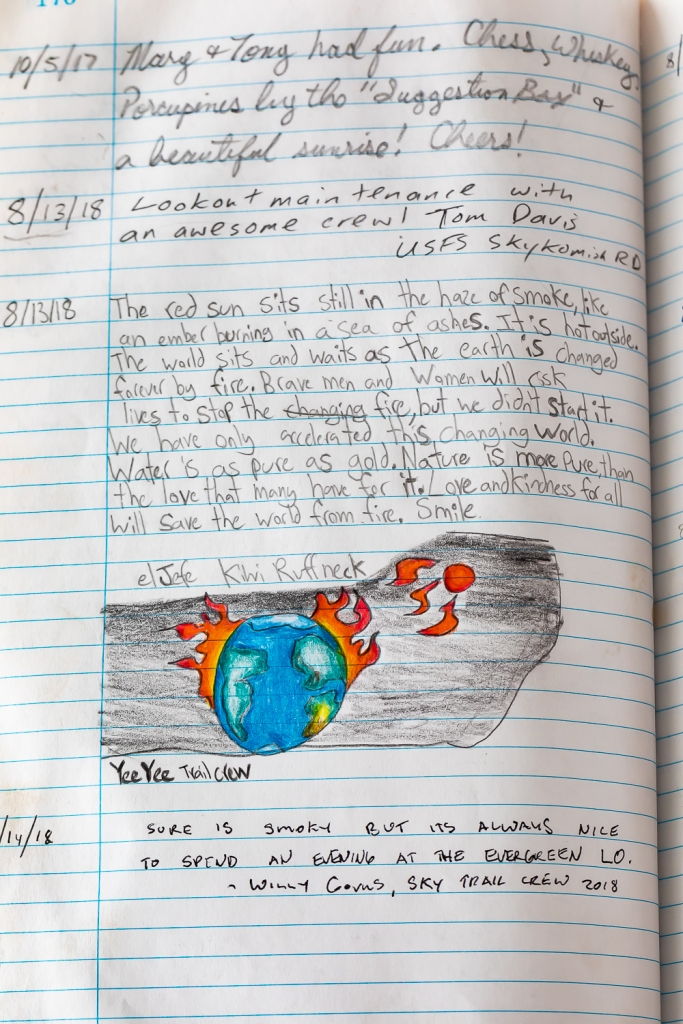

But we weren’t the only ones to have a profound experience here. In looking at the visitor register kept in the lookout, we found that people often wrote poetic passages about their experience with nature in this place. I transcribed some of them here, without names so privacy can be assured, to show how the solitude of an individual or the intimate experience of a small group can be so enthralling.

5 October 2006

“Dinner of steak, rice, and broccoli about 9 p.m. then to bed. By this time the wind was blowing hard. The shutters along the south side of the lookout were bouncing loudly, making a grating noise. Cold out and it was seeking a way inside through every small crack so we tore a towel in strips and chinked the larger cracks. Settle in around 10 p.m. hoping for some sleep.

Extremely strong winds blasted the lookout around 1:30 a.m. and the center support holding the shutters on the south side gave way. The heavy shutters bounced wildly. We worried that all the shutters would fall in and smash the glass down upon us. We got up and placed a tarp and air mattress across the inside of the glass and tried to settle down. Sleep was almost impossible.

Sunrise was around 6:30 and we rose to clear, very cold skies. The wind had not abated and the shutters still bounce in the daylight. We saw that the center support had thrown its top bolt and we were able to replace it. The wind keeps blowing. Two hawks are braving the wind and hunting in the southern meadow.

Wind somewhat easier at noon. Time for a last walk east along the ridge and then out.”

18 September 2009

“Came up to fix a few things reported broken. Unfortunately it was worse than reported. Locks and windows broken, garbage and stuff everywhere. So sad. But we did what we could so hopefully it will last.

Weather was absolutely perfect! Could not have been better. No fog, not too hot, cool wind constantly blowing. The sky was so clear we could see forever in every direction. I can’t believe how many peaks there are!

Thanks so much for allowing me to come up here. It was a perfect trip. And please, please show respect for this place and take care of it.”

9 August 2013

“Lightning and thunder started in the south at about 10:30 p.m. By 12 a.m. all of us were awake from the wind and by about 1:30 a.m. the storm was right above us and lasted until about 3:30 a.m. when the wind picked up again. Very beautiful and terrifying. A once in a lifetime experience.”

2 October 2017

“This is my third time at the lookout, but the first time without human companions. Just me and the dog, seeking solitude and some healing after a death in the family.

I woke up to a stunning sunrise, mountain peaks visible all around but a magical cloud cover down below. Cold though! Icicles on the lookout–glad I had the dog to keep me warm through the night.

Although not healed, the mountains and solo time did me good. Focus on enduring beauty, on the things that knock us breathless and senseless. This helps.”

13 August 2018

“The red sun sits still in the haze of smoke, like an ember burning in a sea of ashes. It is hot outside. The world sits and waits as the earth is changed forever by fire. Brave men and women will risk lives to stop the fire, but we didn’t start it. We have only accelerated this changing world. Water is as pure as gold. Nature is more pure than the love that many have for it. Love and kindness will save the world from fire.”

15 August 2018

“A beautiful smoky day of repairs at the ol’ fire lookout. Met a wonderful woman hiker who used to live in this very lookout almost 40 years ago! The magic of this place is still alive and well!”

15 August 2018

“Smoky. Still a lovely hike, tho seems a lot harder than in the summer of 1976, when I was the lookout here.”

5 September 2018

“Simply beautiful up here. Mountains in every direction, too many to name. Wonderful artwork of nature. Had fun picking huckleberries. Wish we would have stayed the night. Next time. Our 3rd anniversary activity of choice.”

16 September 2018

“A rainy, snowy, cloudy trip and we couldn’t ask for anything more. Had a fantastic time hanging out in the cabin watching the weather. Can’t wait to come back and do it again.”

10 August 2019

“On this day 5 years ago I stayed overnight in 3 Fingers [another lookout]. After going home on the 10th I had a heart attack. Was great to be able to spend the night and celebrate life. If you go to 3 Fingers check out the lightning stool I made for my first year anniversary of the heart attack!”

11 August 2019

“It felt like something out of a storybook to hike up and up into the clouds where you couldn’t see thirty feet ahead or behind you. Wildflowers that I thought I wouldn’t see again this late in the year bloomed along the trailside. It was magical finally seeing the lookout appear out of the mist. Then to wake up surrounded by it just makes me feel like I’m in another world.”

Hikers are not the only people who have found the fire lookout to be an inspiring muse. There is a long tradition of writers who have spent summers working for the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service perched in their mountaintop retreats, looking for smokes while simultaneously thinking and taking notes and working on poems and novels. Without a boss looking over their shoulders, the thoughts could rise from the depths like columns of smoke on a distant ridge.

Gary Snyder, a poet who has written a lifetime of poems of depth, infused with Zen Buddhism and nature, watched the landscape atop Sourdough Mountain Lookout in the North Cascades of Washington in the summer of 1953. His meditative book Riprap and Cold Mountain Poems begins with this gem from that time:

Mid-August at Sourdough Mountain Lookout

“Down valley a smoke haze

Three days heat, after five days rain

Pitch glows on the fir-cones

Across rocks and meadows

Swarms of new flies.

I cannot remember things I once read

A few friends, but they are in cities.

Drinking cold snow-water from a tin cup

Looking down for miles

Through high still air.“

Decades later Tim McNulty, a writer from the Olympic Peninsula, also stayed in Sourdough Mountain Lookout for a season. He found it a profound experience, and wrote evocative poems about his time there. These are included in his book of poetry called Ascendence; here is a wonderful excerpt from one poem

Night, Sourdough Mountain Lookout

“I light a candle with the coming dark.

Its reflection in the window glass

flickers over mountains and

shadowed valleys

seventeen miles north to Canada.

Not another light.

The lookout is a dim star

anchored to a rib of the planet

like a skiff to a shoal

in a wheeling sea of stars.

Night sky at full flood.

Wildly awake.“

Jack Kerouac, writer of the cultural phenomenon On the Road, a vibrating-with-life contrast to the staid and conforming 1950s and early 1960s, worked on Washington’s Desolation Peak Lookout in 1956, a time that inspired some of his work on the books Desolation Angels, The Dharma Bums, and Lonesome Traveler.

“Thinking of the stars night after night I begin to realize ‘The stars are words’ and all the innumerable worlds in the Milky Way are words, and so is this world too. And I realize that no matter where I am, whether in a little room full of thought, or in this endless universe of stars and mountains, it’s all in my mind.” from Lonesome Traveler

Norman Maclean worked on Elk Summit Lookout in Idaho, and later went on to pen Young Men and Fire and A River Runs Through It and Other Stories. These stories captured tragedies in the American West where he made his home.

“In the late afternoon, of course, the mountains meant all business for the lookouts. The big winds were veering from the valleys toward the peaks, and smoke from little fires that had been secretly burning for several days might show up for the first time. New fires sprang out of thunder before it sounded. By three-thirty or four, the lightning would be flexing itself on the distant ridges like a fancy prizefighter, skipping sideways, ducking, showing off but not hitting anything. But four-thirty or five, it was another game. You could feel the difference in the air that had become hard to breath. The lightning now came walking into you, delivering short smashing punches.” from A River Runs Through it and Other Stories

Edward Abbey wrote Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness which became one of my personal guiding lights since the time I first read it as a college freshman over 50 years ago. Abbey writes of his adventures in the old days of Moab, Utah, before it became a recreation mecca. Abbey’s book helped turn Moab into the “industrial tourism” machine that he detested, but I’ll save that rant for another time. Abbey needed to make ends meet, like all of us, so he worked at the Bright Angel Point Lookout on the North Rim of the Grand Canyon for four seasons, where he stationed his typewriter near the Osborne Fire Finder.

“Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, and as vital to our lives as water and good bread. A civilization which destroys what little remains of the wild, the spare, the original, is cutting itself off from its origins and betraying the principle of civilization itself.”

“No more cars in national parks. Let the people walk. Or ride horses, bicycles, mules, wild pigs–anything–but keep the automobiles and the motorcycles and all their motorized relatives out. We have agreed not to drive our automobiles into cathedrals, concert halls, art museums, legislative assemblies, private bedrooms and the other sanctums of our culture; we should treat our national parks with the same deference, for they, too, are holy places.” both quotes from Desert Solitaire

Fire lookouts, and hikes, and long bike rides, and long road trips: times and places that are apart from the rest of life. Places and times to think deeply, to breathe in the subterranean thoughts swirling up from our brains and the soil and the landscape.

Good Links:

Art on High: Beat Poets on the Fire Lookouts about Gary Snyder and Jack Kerouac and others

LOOKING OUT, LOOKING IN: GARY SNYDER AND SOURDOUGH MOUNTAIN LOOKOUT an excellent blog about Snyder and his writing

Poems from Sourdough Mountain Lookout by Tim McNulty, a prominent Olympic Peninsula writer

Climbing a Peak That Stirred Kerouac by a New York Times writer

Fire Tower at Bright Angel Point the tower where Edward Abbey stayed above the Grand Canyon

A Fire Lookout On What’s Lost In A Transition to Technology an NPR interview with Philip Connors, author of Fire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness Lookout